What Remains of the 14th and Early 15th Centuries?

- Aidan Drohan

- Feb 17, 2022

- 4 min read

Updated: Feb 18, 2022

Although most of what was built and created in the fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries has been lost to time due to renovations of cities and the primitive structure of most buildings, we are lucky enough to experience a great wealth of culture and architecture that remains in France, giving us a glimpse into what life during the fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries may have looked like. Almost every medieval city in France is home to a cathedral or multiple cathedrals, each with its own unique and distinctive artistic and architectural design. Most cathedrals in existence today started construction in the late 13th century, the majority of what we see today being additions constructed in the 14th and early 15th centuries. What is paramount are the stories that the engravings, religious art, and stain glass windows tell us about the communities who constructed these cathedrals over many generations, and what they faced as a community and principality.

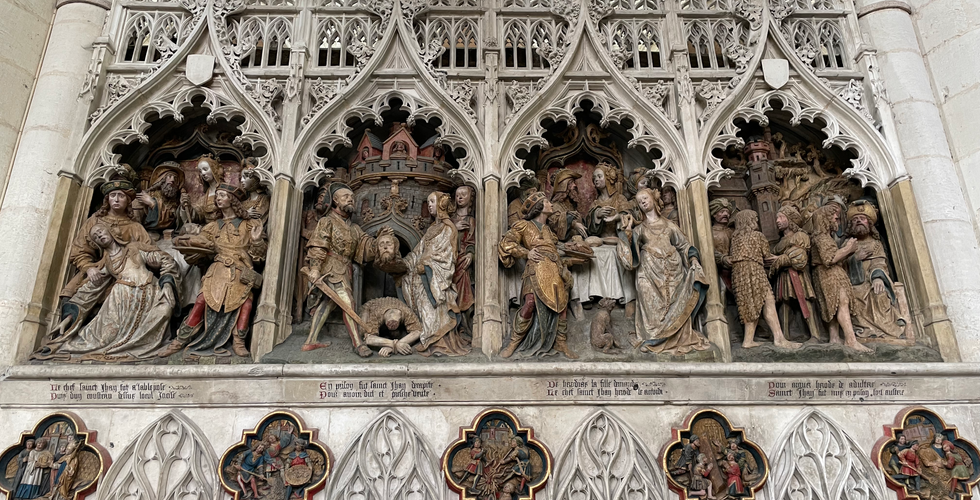

The Cathedral of Amiens, my personal favorite, was even constructed during the Hundred Years War, proving to be a well known site to both the English and the French for the wars duration. Amiens is also the site where Philip VI amassed his army before Edward III’s Crécy Campaign. One cannot help but to imagine the great historical figures who have stepped into the cathedral and walked upon the very stones you stand upon. The interior of the cathedral includes original 15th century wood carvings depicting the story of Saint John the Baptist and the life of Saint Firmin, the patron Saint of Amiens. These carvings serve as a reminder of how religion played such a central role in the lives of the medieval population of Europe. The nave of the cathedral, the beautiful arched arcades which rest upon circular pillars surrounded by four colonnettes, was built during the 1370’s, and still serves as a beautiful and distinctive aspect of the cathedral’s interior. The chapels on the western facade were also built during the Hundred Years War, representing some of the oldest examples of the flamboyant style in northern France. The engravings and portals etched into the cathedrals exterior depict the story of the passion, also bringing well known saints and biblical characters to life much like the exterior of Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris.

Another fascinating cultural relic from the 14th century is the Apocalypse Tapestry located in the city of Angers. Angers was the seat of the Plantagenet dynasty, the tapestry being stored in Chateau d’Angers which was constructed by the Plantagenets in the early 13th century. The tapestry itself was commissioned by Louis I, Duke of Anjou in 1373 and tells the story of the French people in the 14th century. Although segments have been lost, the tapestry is still in amazing condition, mainly depicting Saint John’s descriptions in Revelations in the New Testament with many allegories to 14th century France. The most notable allegories in the Apocalypse Tapestry are Edward the Black Prince on one of his many Chevauchée campaigns against the French people, a depiction of death riding a pale horse to illustrate the great effect that the plague had upon the whole of medieval society, and pestilence riding a black horse which followed the plague and effected France throughout the Hundred Years War.

But the most amazingly preserved relic of 14th and early 15th century life may be Mont Saint Michel in the Normandy region of France, a fortified abbey which has held religious significance since the 8th century AD. The construction of the village’s fortifications started in the mid 13th century, but almost all of what we see today can be attributed to investments in defensive structure as a direct result of the Hundred Years War. In 1386, renovations of the outer defensive works and the demolition of buildings which could interfere with the abbey’s defense were undertaken, and fortifications built on the southwestern escarpments which had previously not been defended. Most notably in 1417 abbot Robert Jolivet commissioned an enormous series of fortifications surrounding the extra mural parts of the village as a result of English aggression. The Kings Gate, the inner most gate guarding the entrance to the village, was also constructed the same year, including a ditch, drawbridge, portcullis, and iron branded oak gates which were state of the art defensive works of the time. The late 14th century also saw the abbey itself, which is built upon the highest escarpments of the village, take upon the role of the village’s keep as a “fortress abbey”. At this time the Châtelet (a small fortified gate) and a barbican were added to the entrance of the abbey, officially altering the abbey to accommodate a defense if necessary. It is truly fascinating to experience what remains physically and culturally from the 14th and early 15th centuries, and how it can influence the times we live in now. In a time of such uncertainty ourselves, we must remind ourselves that goodness always prevails, as the Apocalypse Tapestry so beautifully displays.

Comments